Park Street Church

On the Freedom Trail

The Park Street Church Freedom Trail Site is currently closed and will reopen for the 2025 summer season.

Visit us on Instagram!

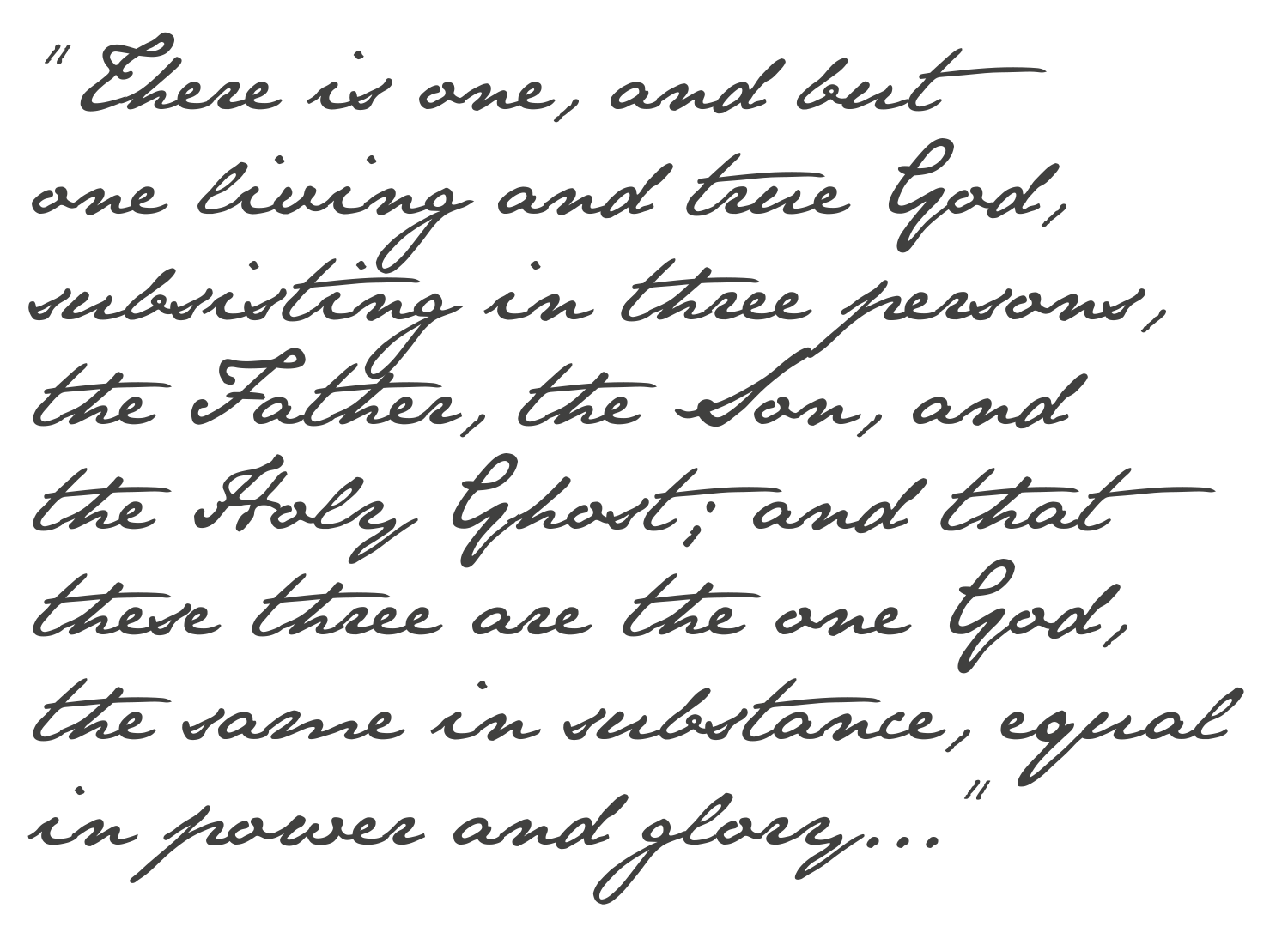

With these words the founders of Park Street Church pronounced the standard upon which they could not compromise: Jesus Christ was no mere messenger sent from God—He was God himself. This stance on the divinity of Jesus had fallen out of favor in the early 1800s, in favor of the doctrine of Unitarianism. Unitarians believe that Jesus was a good moral teacher rather than being one with God Himself. The election of Henry Ware, a firm Unitarian, to the chairmanship of Harvard Divinity School in 1805 confirmed the momentum of the “Unitarian wave.” At its founding, Park Street Church found herself only one of only two churches out of 17 in Boston that still rigorously adhered to belief in the tri-personal nature of God.

With these words the founders of Park Street Church pronounced the standard upon which they could not compromise: Jesus Christ was no mere messenger sent from God—He was God himself. This stance on the divinity of Jesus had fallen out of favor in the early 1800s, in favor of the doctrine of Unitarianism. Unitarians believe that Jesus was a good moral teacher rather than being one with God Himself. The election of Henry Ware, a firm Unitarian, to the chairmanship of Harvard Divinity School in 1805 confirmed the momentum of the “Unitarian wave.” At its founding, Park Street Church found herself only one of only two churches out of 17 in Boston that still rigorously adhered to belief in the tri-personal nature of God.

Trinity — One God who exists in three persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Sprit.

The Original Granary

The Granary, built in 1729, in addition to being a location to store grain, was also home to the creation of the sails for the U.S.S. Constitution before finally serving as a petting zoo. After the purchase of the land in 1809, its timbers were moved Commercial Point in Dorchester (the site of the Boston Gas Tank), where it served as a ship equipment storehouse and, at the time this photograph was taken in 1873, was being used as a hotel.

The revival period of the Second Great Awakening was underway, and suddenly large formerly-unchurched crowds were looking for a home. A small group at the Old South Church, keen on both preserving the doctrine of the trinity and promoting revival, resolved to establish an uncompromisingly orthodox church in the very center of the Boston peninsula. They were inspired by a visiting minister, Rev. Henry Kollock from Savannah, GA, and invited him to be their first shepherd. Rev. Kollock was inclined to accept, but said he would not move until a church was organized and a building constructed. The committee immediately purchased a plot of land on the corner of the site of the old Granary building, but after construction began, Kollock decided not to come.

It was a disappointing and embarrassing initial blow for the small congregation, which had raised $70,000 to build what was plausibly the grandest church in the city at the time. Seating over 800, the building had been designed by Peter Banner in a style similar to that of Christopher Wren. The steeple was erected around a strong and flexible ship’s mast, and at 217 feet made Park Street the tallest building in the United States for 36 years (until the construction of Trinity Church in New York) and in Boston for 57 years (until the construction of the Church of the Covenant). The large, brand-new sanctuary now sat without minister or congregation, and to some critics the fledgling endeavor already seemed like a failure.

The Devil and a Gale of Wind

Danced hand in hand up Winter Street.

The Devil like his demons grinned

To have for comrade so complete

A rascal and a mischief-maker

Who’d drag an oath from any Quaker.

The Wind made sport of hats and hair

That ladies deemed their ornament;

With skirts that frolicked everywhere

Away their prim decorum went;

And worthy citizens lamented

The public spectacles presented.

The Devil beamed with horrid joy,

Til to the Common’s rim they came,

Then chuckled, “Wait you here, my boy,

For duties now my presence claim

In yonder church on Brimstone Corner

Where Pleasure’s dead and lacks a mourner;

“But play about till I come back.”

With that he vanished through the doors,

And since that day the almanac

Has marked the years by tens and scores,

Yet never from those sacred portals

Returns the Enemy of Mortals.

And that is why the faithful Gale

Round Park Street Corner still must blow,

Waiting for him with horns and tail—

At least some people tell me so—

None of your famous antiquarians,

But just some wicked Unitarians.

~ M. A. DeWolfe Howe

Despite initial setbacks, the congregation’s original commitment had not been superficial. The group invited Edward Dorr Griffin, a professor at Andover Theological Seminary, to be their pastor. He agreed, and his ministry left an indelible mark of doctrine and missions on the church. After pastoring Park Street, Griffin became the president of Williams College.

The establishment of the American Board of Foreign Missions is deeply intertwined with Dr. Griffin and Park Street Church. “[T]his relation which has existed between us is not a relation alone between one organization and another. We were born together, as has been said, the Board and Park Street Church, the children of one mother…”

Although individual support for missions was common at the time, Griffin’s church-wide backing of some of the earliest missionaries sent out from the United States is believed to be a first. On October 15, 1819 at Park Street Church, fifteen people bound for the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) were given official recognition as the “Sandwich Islands Church.” The relationship between Park Street Church and the resulting Hawaiian churches—Mokuaikaua Church in Kailua Kona, Kawaiaha’o Church in Honolulu, and Waimea Church in Kauai—continues to this day. In October 2019, a bicentennial celebration at Park Street Church included many representatives from these churches.

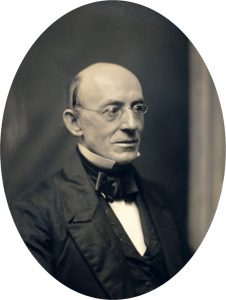

With Park Street’s zeal for the spread of the Gospel throughout the world, it did not neglect its own neighborhood. In subsequent years numerous improvement societies originated there, including the American Education Society, the Boston chapter of the NAACP, the Animal Rescue League, the Prison Discipline Society, and the American Temperance Society. William Lloyd Garrison gave his first antislavery address from that pulpit on July 4, 1829. Two years later a children’s choir performed the hymn “America” (My Country, ‘Tis of Thee) set to music by Park Street’s own director of music, Lowell Mason.

“Before God, I must say that such a glaring contradiction as exists between our creed and practice the annals of six thousand years cannot parallel. In view of it I am ashamed of my country. I am sick of our unmeaning declamation in praise of liberty and equality, of our hypocritical cant about the unalienable rights of man. I could not, for my right hand, stand up before a European assembly, and exult that I am an American citizen, and denounce the usurpations of a kingly government as wicked and unjust; or, should I make the attempt, the recollection of my country’s barbarity and despotism would blister my lips, and cover my cheeks with burning blushes of shame.” (William Lloyd Garrison, in his first Anti-Slavery Address at Park Street Church in Boston, July 4, 1829.)

“Before God, I must say that such a glaring contradiction as exists between our creed and practice the annals of six thousand years cannot parallel. In view of it I am ashamed of my country. I am sick of our unmeaning declamation in praise of liberty and equality, of our hypocritical cant about the unalienable rights of man. I could not, for my right hand, stand up before a European assembly, and exult that I am an American citizen, and denounce the usurpations of a kingly government as wicked and unjust; or, should I make the attempt, the recollection of my country’s barbarity and despotism would blister my lips, and cover my cheeks with burning blushes of shame.” (William Lloyd Garrison, in his first Anti-Slavery Address at Park Street Church in Boston, July 4, 1829.)

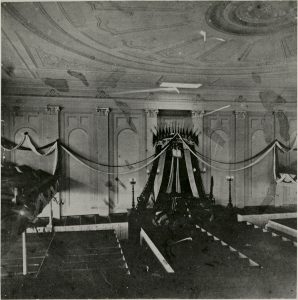

In 1862, in answer to President Abraham Lincoln’s call to arms, 80 men from the pews of Park Street Church joined the 45th Massachusetts Regiment. Pastor Andrew Stone agreed to serve as chaplain. Several heartbreaking wartime letters to the congregation live today in the archives at the Congregational Library: “Let your prayers hover constantly over the pillows of our sick and wounded. The touch of loved fingers is far away, but your intercession may be as the shadow of an angel’s wing to faces growing white under the signature of death.” He returned home after eight months of service to a motivated church. The Woman’s Benevolent Society c ontributed bandages, socks and food items for soldiers. The church also supported local chapters of the Christian Commission and the YMCA. The joyful news of the surrender at Appomattox was eclipsed by the shock of the assassination of President Lincoln. The congregation, prepared to rejoice, was wrenched into lament instead. A photograph of the sanctuary draped in yards of black mourning cloth preserves the grief the church felt at the announcement.

ontributed bandages, socks and food items for soldiers. The church also supported local chapters of the Christian Commission and the YMCA. The joyful news of the surrender at Appomattox was eclipsed by the shock of the assassination of President Lincoln. The congregation, prepared to rejoice, was wrenched into lament instead. A photograph of the sanctuary draped in yards of black mourning cloth preserves the grief the church felt at the announcement.

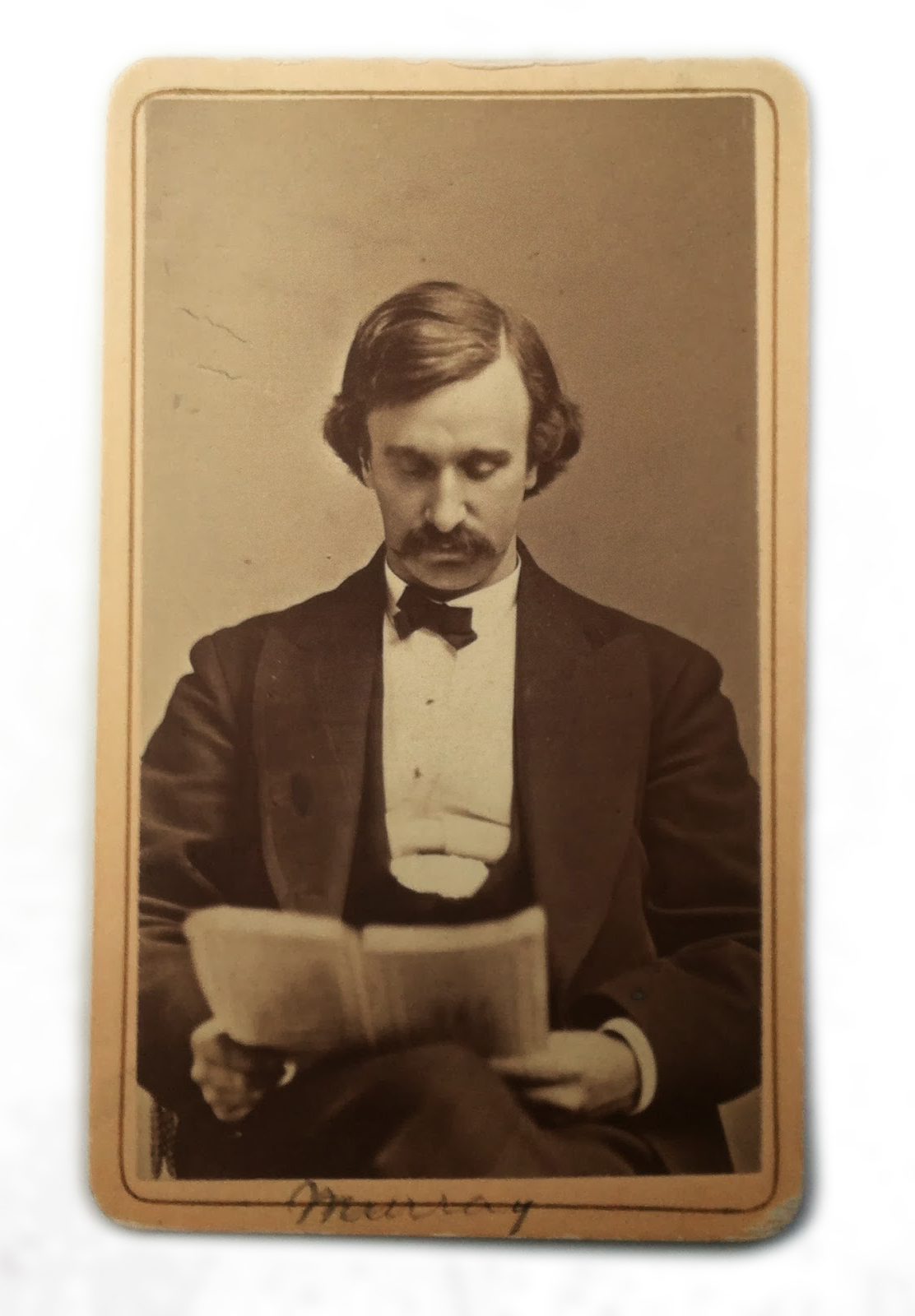

In 1868, the church installed William Henry Harrison Murray— “unquestionably the most unique individual ever to pastor Park Street Church.” Dubbed “Adirondack Murray,” he lectured on Sunday evenings about the Adirondack wilderness of New York, and published Adventures in the Wilderness, or, Camp-Life in the Adirondacks the year after he was hired. (This publication is credited as the pivot from the British usage of the word “holiday” to the adoption of the American term, “vacation.”)

A hot-blooded and zealous preacher and adventurer, he felt constrained by the aristocratic and intellectual personality of the members of Park Street Church. Murray intensely desired that the church focus on the poor and outcast around them. Finally, his differences with the Park Street deacons having become irreconcilable, he resigned in 1874, only to immediately open his “New England Church” a stone’s throw away in what is now the Orpheum Theatre.

Startled at this news, a group of Bostonians unaffiliated with the church rapidly formed a “Committee for the Preservation of Park Street Church,” arguing that the historical value, cultural influence and architectural beauty of the church had inestimable worth to the city of Boston and should be preserved by all possible means. (For example, even the geographic location was honored by Back Bay architect Ralph Huntington —as in “Huntington Avenue”— who directed that Columbus Avenue, the spine of the Back Bay project, aim directly for the Park Street Church steeple.)

The ensuing years were marked by a noticeable demographic shift to the suburbs, and the church building was surrounded and nearly blocked by years of subway construction. The decline in attendance forced the church to rent out space in its basement to street-level vendors, which served to stall a seemingly inevitable downturn. On December 11, 1902 the Park Street Congregational Society officially voted to sell the church building, believing that the money received from the purchase could be used to relocate to a more convenient location. The Boston Herald jumped at the chance, offering $1.25 million and announcing plans to tear down the church and replace it with an 11-story office building.

125th Anniversary Radio Clip

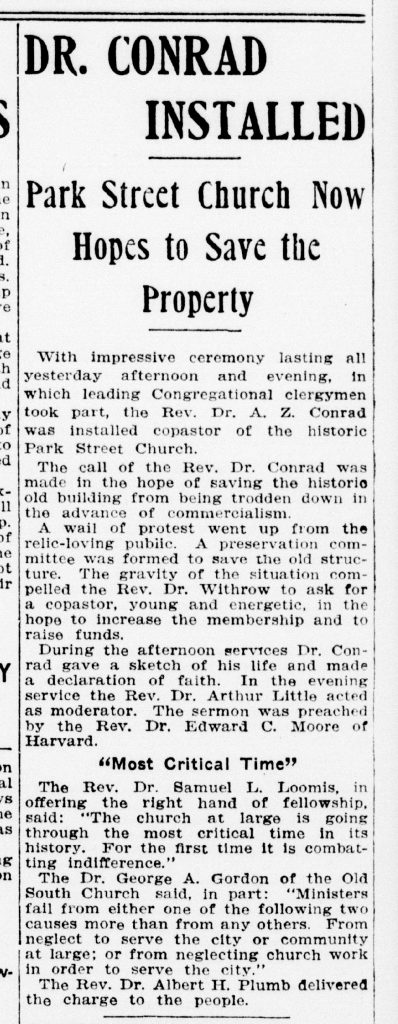

Perhaps due to pressure from the public outcry in combination with the loss of confidence in the real estate market, the deal fell through.18 The pastor of Park Street, Dr. John Withrow, had a change of heart and asked the membership to hire a new associate minister who could reenergize the church. Dr. Arcturus Zodiac Conrad accepted the position in October 1905.

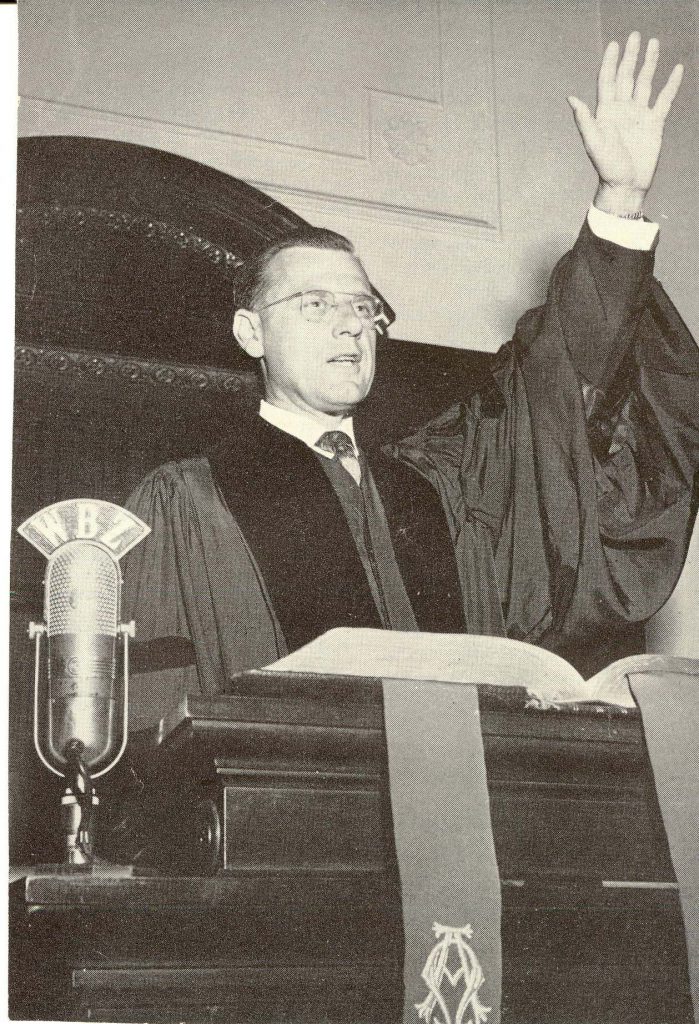

Perhaps no one could have been better suited to initiate the church into the modern era than A.Z. Conrad. As aggressive in business as he was in theology, Conrad capitalized on the recent goodwill of the city and began a series of improvements, which included remodeling the front of the sanctuary, the purchase of a new organ and the removal of decades of gray paint from the original red brick exterior. “After three years of ministry, the Sunday morning crowds had more than doubled; the number in the evening services had quadrupled. As soon as it was possible, on January 14, 1923, Park Street Church sermons were broadcast over the newly incorporated airwaves of WNAC. Conrad’s contribution not only to Park Street Church, but also to American evangelical history in general may have been more present in the public mind, if not for the enormous visionary influence of his chosen successor, Harold John Ockenga.

From the start Ockenga showed a tendency toward overachievement. During his first senior pastorate at Point Breeze Presbyterian in Pittsburgh, PA, he grew the Sunday school to over 400 people, added a 60-voice choir and retired the mortgage, all while working toward a PhD in economics at the University of Pittsburgh (his dissertation was entitled, “Poverty as a Theoretical and Practical Problem of Government in the Writings of Jeremy Bentham and the Marxian Alternative”).

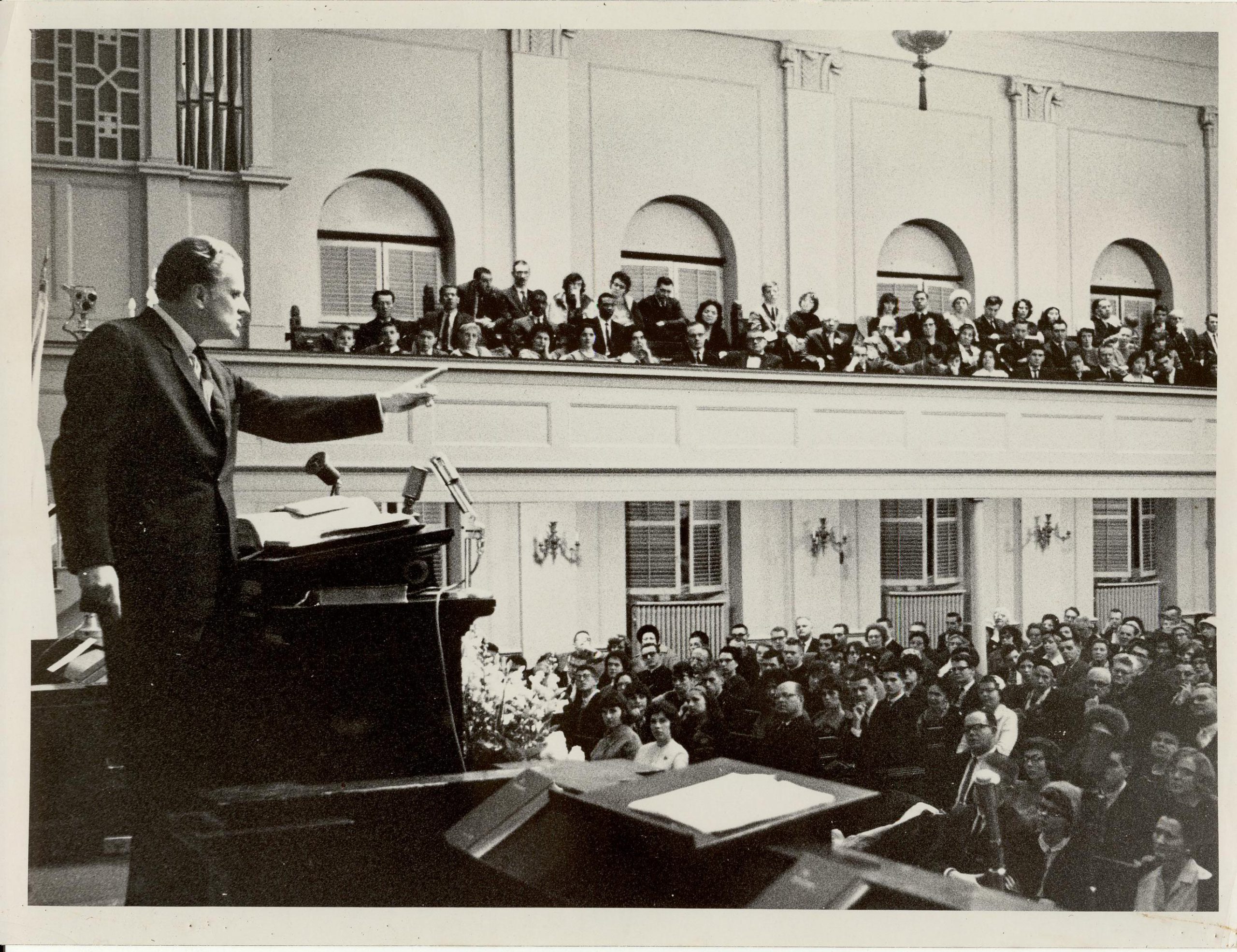

Ockenga had a deep love for Boston, and Park Street Church turned out to be an ideal site from which he could launch his initiatives. While serving as senior pastor, Ockenga helped organize Christianity Today magazine, was the founding president of the National Association of Evangelicals, founded the War Relief Commission (now World Relief), was a founding father and the first president of Fuller Theological Seminary, was host to an unprecedented Billy Graham crusade in 1950, and authored 12 books. After his retirement he orchestrated the merger of Gordon Divinity School and Conwell School of Theology and served as the first president of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.

Ockenga’s worldview was conceived against the backdrop of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy at Princeton Theological Seminary, where he began his theological education. When his professor and mentor, John Gresham Machen, left the inhospitable environment at Princeton to found Westminster Theological Seminary, Ockenga followed, graduating from Westminster in 1930. (Even the hymnal we continue to have in our sanctuary pews today is that of the Orthodox Presbyterian denomination—established by Machen in 1933.)

The tie binding these incredible accomplishments was Ockenga’s sincere faith in the God of the Bible. He feared neither the reality of the supernatural, considered absurd by academic peers in Boston, nor the rigorous intellectual practice viewed as dangerous by fellow fundamentalists. His “neo-evangelical” commitment to theological orthodoxy flowed deliberately into a pragmatic lifestyle devoted to serving the whole person—soul, mind and body.

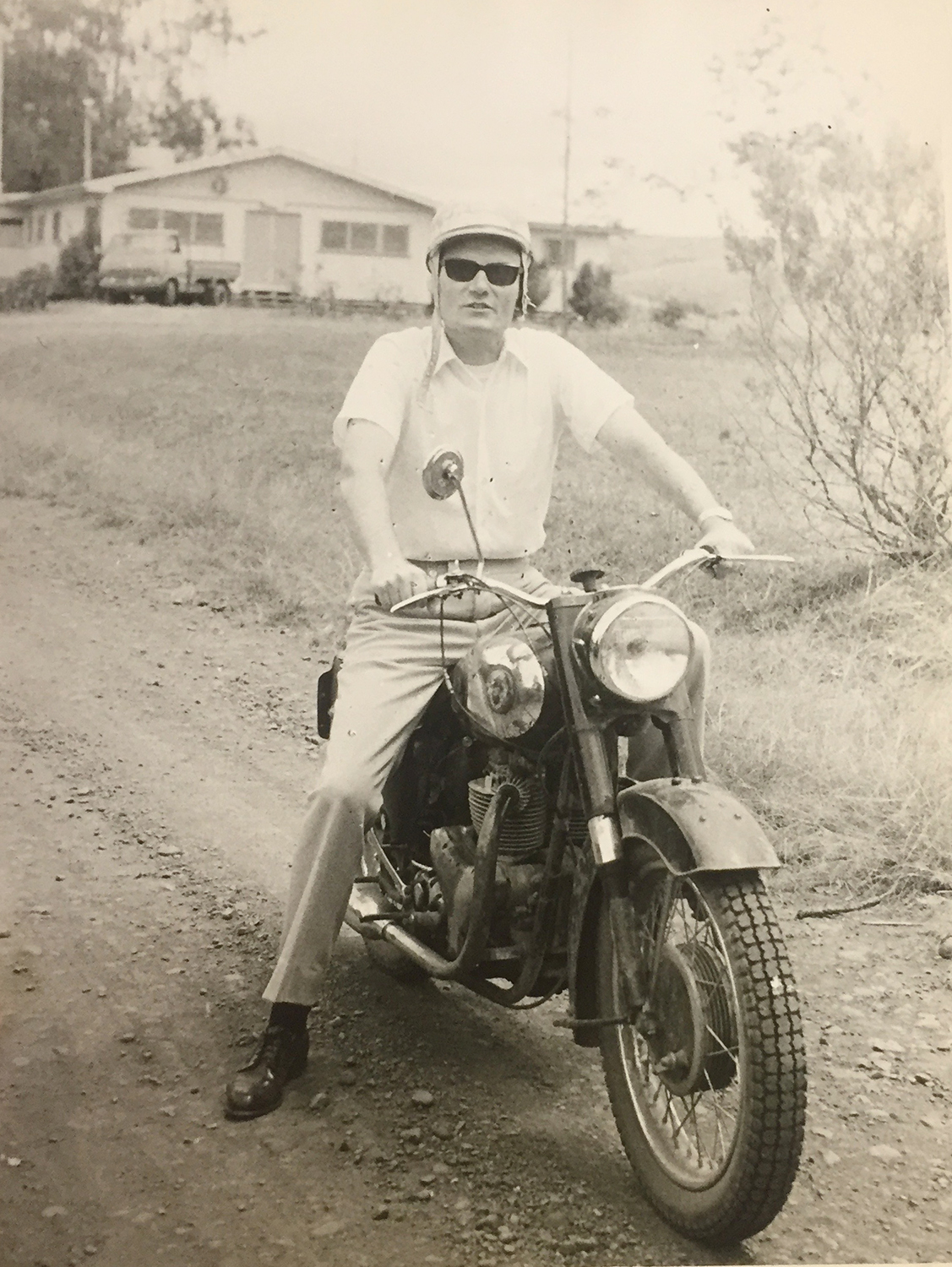

Dr. Paul E. Toms, Ockenga’s associate minister and eventual successor, was himself something of a product of Park Street Church’s missions history. Before coming to Boston he and his wife, Eva, served as missionaries in Hawaii, even for a time pastoring the very church started by those early missionaries to the Sandwich Islands. His passion for world missions matched Ockenga’s, and during his tenure as senior minister Park Street’s relationship with its missionaries deepened.

Another turn of a century approached, and the next senior pastor David C. Fisher embraced it. He encouraged associate minister Daniel Harrell to form a contemporary/ postmodern service in the evening, eagerly embraced by the next generation. Growth was dramatic. Years later a lengthy expose in the Boston Globe reported: “Park Street is the flagship church for college evangelicals from about 20 campuses in the Boston area. Ten years ago, the church’s traditional Sunday night service was attracting only 40 people and was about to be canceled. Church leaders instead decided to refashion it to suit college students and partnered with Campus Crusade and InterVarsity. These days, more than 1,000 students show up at Park Street most Sunday evenings. Church leaders have had to expand to two services.”

David Fisher’s innovations expanded beyond just the worship services. He encouraged the integration of computers in the office, wired the sanctuary for sound, increased pay for female church employees to equitable levels, and purchased numbers two and three Park Street from neighboring Houghton Mifflin Publishers. Fisher urged a 20th century church into a 21st century mindset.

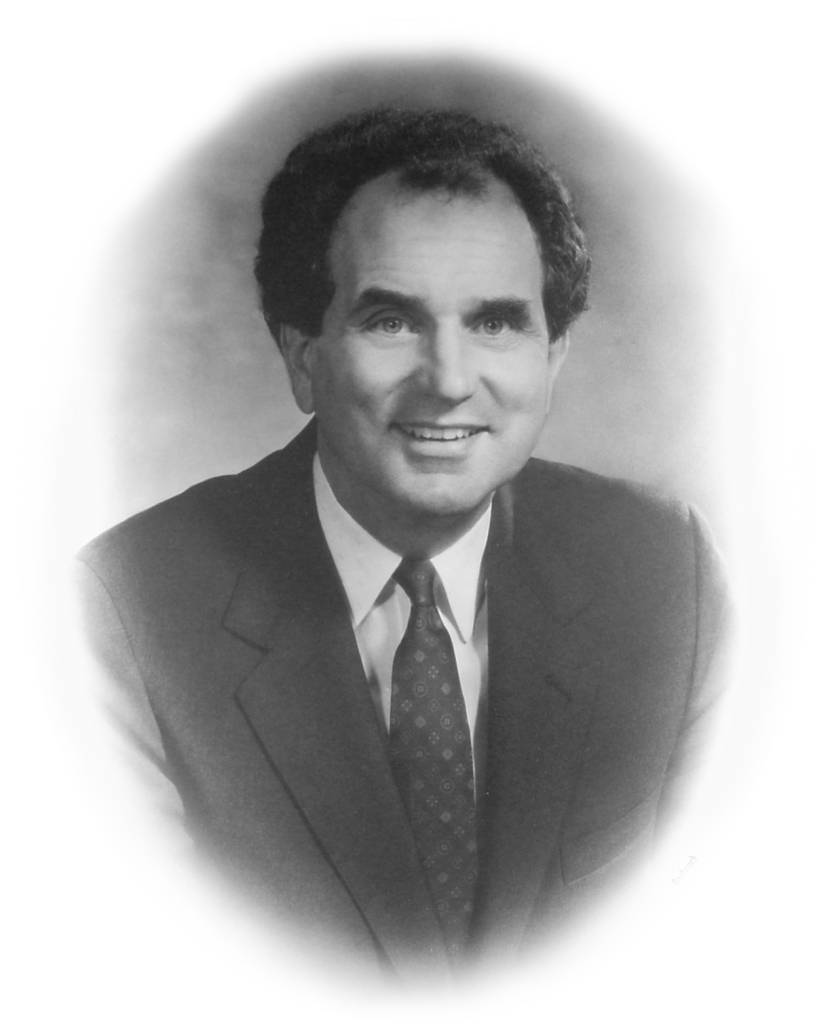

Park Street’s most recent senior minister, Gordon P. Hugenberger is a true native son of New England, and in some ways, of Park Street Church itself. Although having come to a saving faith through the work of the Salvation Army, Hugenberger sat through Harold Ockenga’s sermons as a young college student of engineering and applied physics at Harvard University. Ockenga’s preaching profoundly affected the way that Hugenberger himself thought about ministry. During his tenure at Park Street Church, Gordon Hugenberger heavily promoted Ockenga’s definition of the “neo-evangelical”—encouraging his congregation to both think and love deeply. He frequently could be heard quoting the motto: “the pursuit of God in the company of friends.”

Although history has yet to be fully realized, Hugenberger is likely to be mostly remembered for his exegetical approach to understanding Scripture and his passion for integrating faith and science. Among his most notable accomplishments is a shift from partial support of foreign missionaries to the adoption of a “full support” or “staff missionary” strategy, targeting the most unreached parts of the world. He also facilitated the birth of two local schools: Park Street School and Boston Trinity Academy. During the 200th anniversary celebration of Park Street Church, Hugenberger presided over a yearlong celebration that included preaching from Joni Eareckson Tada, John Piper, Francis Collins, and others.

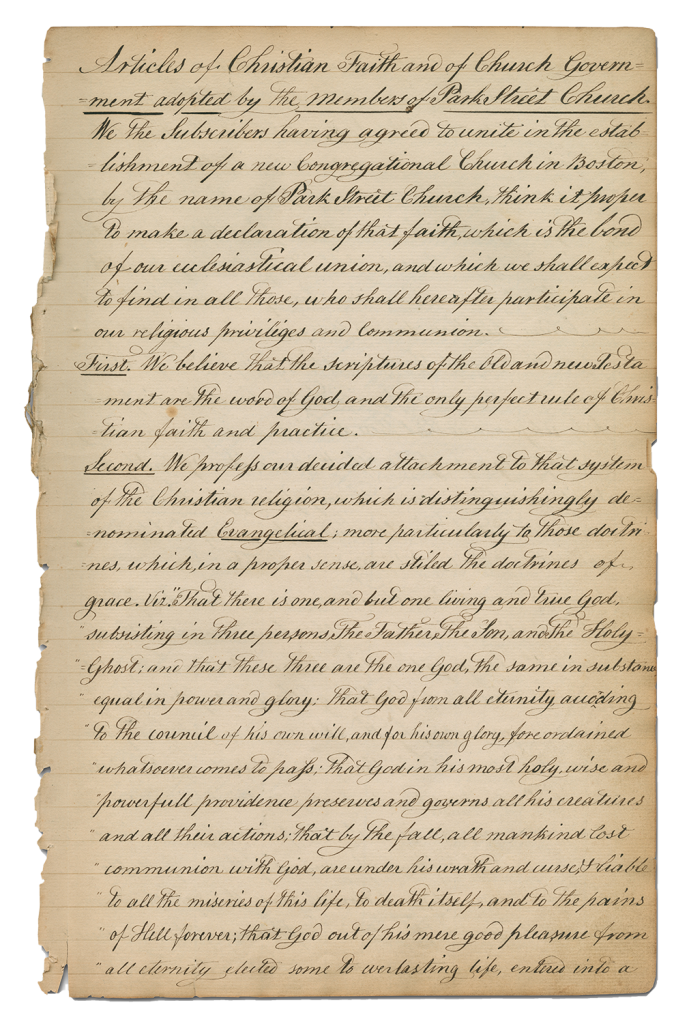

Throughout the years, Park Street Church has remained remarkably consistent in its dedication to worship in spirit and in truth. Although culture and politics fluctuate locally and globally, the words of the original members’ commitment abide:

“Finally, we hereby covenant and engage as fellow Christians, of one faith, and particulars of the same hope and joy, to give up ourselves unto the Lord, for the observing the ordinances of Christ together with the same society, and to unite together into one body, for the public worship of God, and the mutual edification of one another, in the fellowship of the Lord Jesus; exhorting, reproving, comforting and watching over each other, for mutual edification, looking for that blessed hope and the glorious appeasing of the great God, even our Saviour Jesus Christ, who gave himself for us, that he might redeem us from all iniquity, and purify unto himself a peculiar people, zealous of good works. Boston February 27th Anno Domini 1809.”